During my reading of Jackie, it has become clear that mental health issues were prevalent in so many of the reader’s lives. However, they were not called mental illnesses, nor were the words mental health, depression, anxiety, or any other of the plethora of mental illnesses used. The only mental illness I have found spoken about is anorexia which links into the focus of body image throughout the rest of the magazine.

In recent years, we have been inundated with buzz phrases such as “it’s okay to talk” and “reach out” with the more people talking about mental health helping to normalise the conversation. The readers of Jackie however, were not faced with this, but instead a narrative that these problems were their own fault. Serious issues are often dealt with, including what I believe would now be considered the warning signs of depression, anxiety, domestic abuse and eating disorders but they are treated with dismissal or skirted around.

Jackie places the issues in plain sight but does not talk about them for what they are, as then it could have been considered to push boundaries of what was appropriate for its readership. Furthermore, these issues were taking place in the domestic environment providing a contrast to the rose-tinted approach Jackie takes throughout the magazine to growing up a girl and the enjoyment found within the home from domestic tasks.

In this post, I would like to talk about one of the two issues I consider to be the most problematic, the presentation of dieting versus anorexia. You’ll have to come back next week for the second. However, I, and yourselves as the reader must place these issues into context. It would be wrong of me to say the way Jackie dealt with mental illness, although hard to read is inherently wrong, as I imagine during the 60s & 70s, the “conversation” was non-existent and the attitude towards mental health was in no way as open as it is today.

Body image, anorexia and hypocrisy

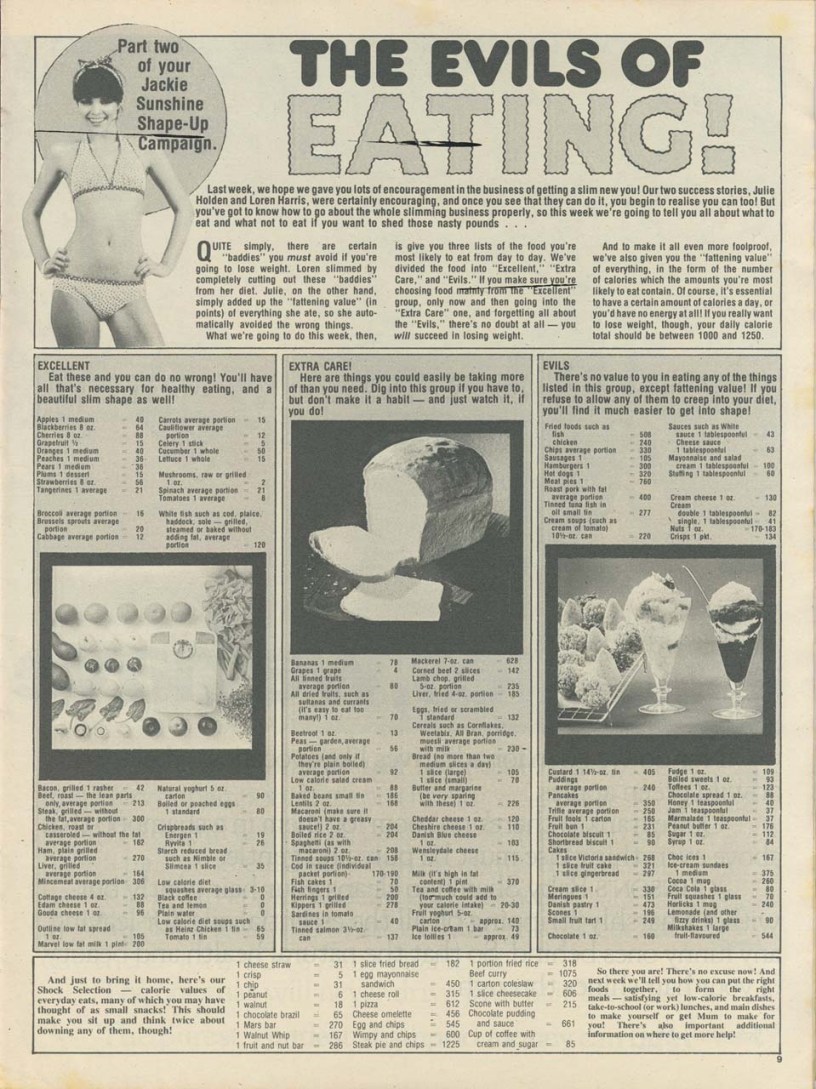

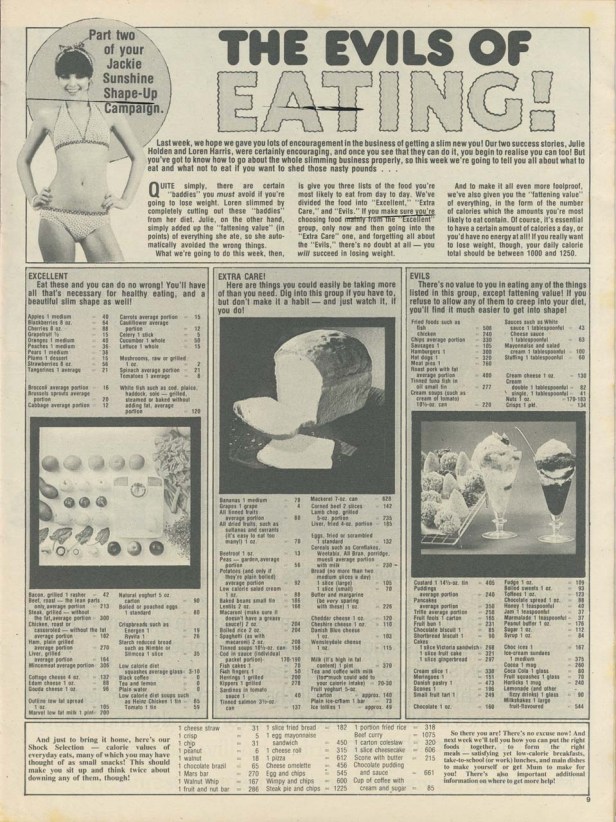

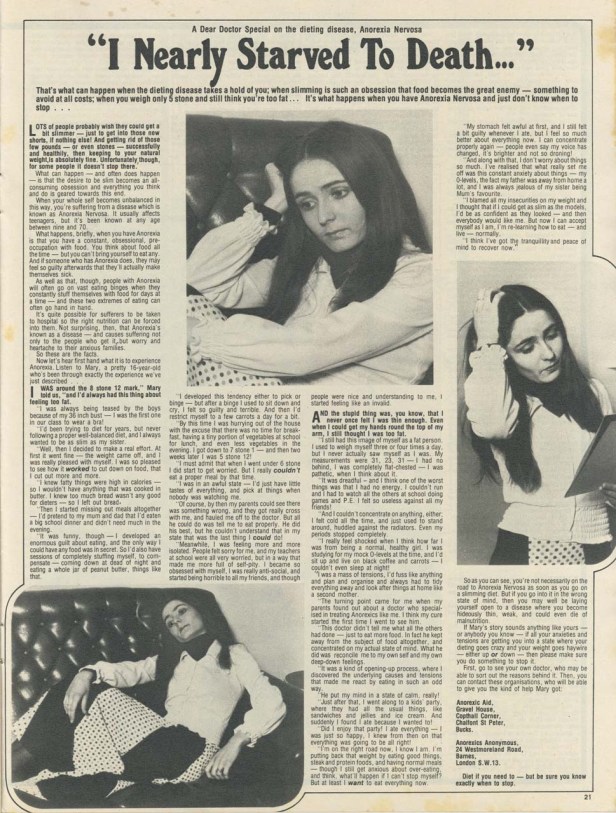

Jackie, particularly in the 70s were obsessed with anorexia or as they called it back then ‘the dieter’s disease’. This is interesting when you consider the number of features which encouraged its readers to diet and exercise or even which shamed them for the inevitable changes to the body during puberty. Being overweight was just about the worst thing a Jackie reader could be and they were constantly encouraged to lose weight through recipes suitable for diets, diet company advertisements and exercises suitable to be completed within the home.

I don’t always agree with the narrative which circulates around celebrities such as the Kardashians or the Love Island stars and social media being the cause of body-image issues in teenage girls as clearly this has been a problem for years. We need to look at what came before and my answer to this is girl’s magazines.

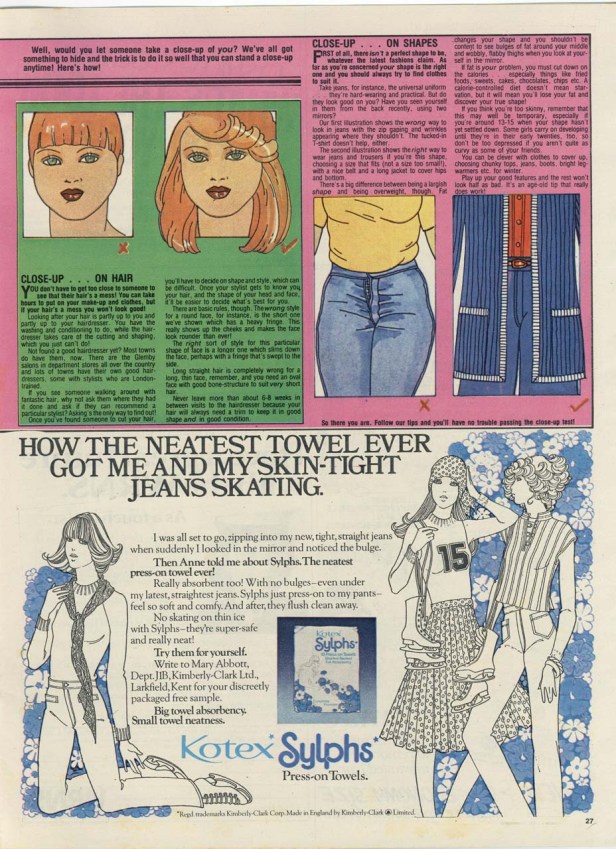

The 3rdof September 1977 titled a feature ‘Close up on Shapes’ which focuses on how to look good in jeans. The reader is told ‘There is a big difference between being a largish shape and being overweight […] you shouldn’t be content to see bulges of fat around your middle and wobbly flabby thighs’ with two illustrations on the ‘right’ and the ‘wrong’ way to look in jeans. The paragraph after however, says not to get disheartened if you aren’t as curvy as your friends. The line between what Jackie sees as ‘curvy’ and therefore acceptable and ‘overweight’ is minuscule. The only difference I see in these pictures is the ‘wrong’ girl has bad posture whilst the ‘correct’ girl is stood up straight leaving her looking slimmer. It reminded me of a current trend on Instagram where fitness stars post ‘Instagram versus reality’ shots showing how lighting, posture and time of day can affect how our bodies look. Returning to the “conversation”, we now live in a society which recognises that not even the models look like models but for the Jackie reader they may have been led to believe they needed to ‘lose fat to discover their true shape’ even if their true shape was changing minute by minute as that is what growing up a girl meant.

(Jackie, 3rd September, 1977)

(Chessie King Instagram, June 5th 2018)

Healthy weight loss for health and wellbeing is not encouraged. If you are slim you are attractive and will look good in the latest fashion and this is the most important factor in remaining a ‘healthy’ weight. The discourse that surrounded food was one that separated food items into good and bad categories using calories and leading to feelings of guilt surrounding food (not too dissimilar to the likes of Slimming World and Weight Watchers today). At the bottom of this ‘evils of eating’ feature there is a shock value section on the calorie content of everyday favourite food items and then they are told that next week there will be meal ideas for their mother to make. Jackie is aware enough that their readers are young girls to suggest a mother will be making their meals and yet circulate an irresponsible and dangerous discourse of eating.

(Jackie, 14th May, 1977)

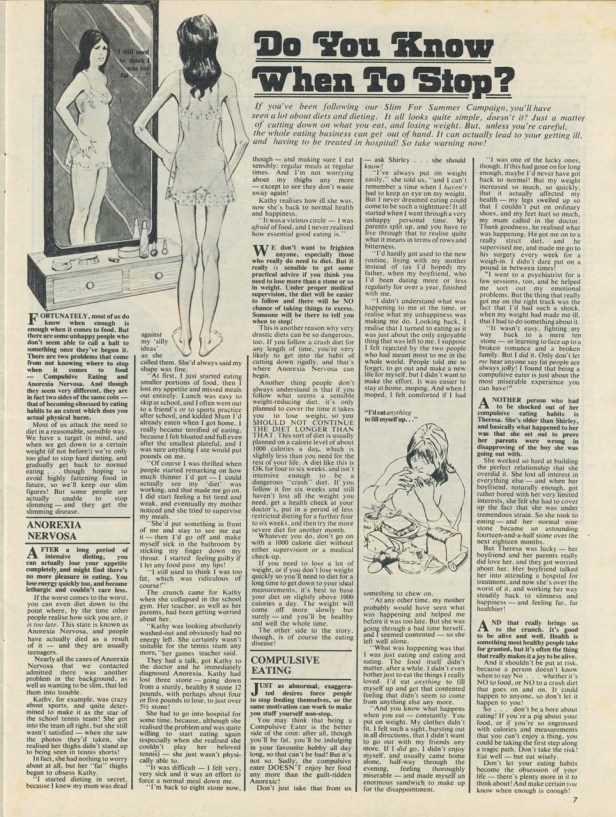

They then wonder why so many girls took dieting too far, ending up ill with ‘dieter’s disease’, now formally and more appropriately named anorexia. This ‘Do You Know When to Stop Feature?’ literally says you will have seen a lot about diets in the magazine but to be careful as it can lead to illness. Jackie aimed to encourage healthy weight loss but from the way they constantly addressed anorexia and other eating disorders it is evident that they failed at this. The use of the reader’s true experience may have been to act as a deterrent of taking the dieting too far, but to me it is the sad reality of the previously mentioned discourse of guilt surrounding food, making teenage girls feel like they were ‘never once […] thin enough’.

(Jackie, 20th August, 1977 and Jackie, 22nd May, 1976)

By Rosie Steele.