LJMU Special Collections & Archives have collaborated with LJMU School of Nursing and Advanced Practice in the Faculty of Health to produce a timeline of Liverpool’s healthcare history at the Tithebarn Street building, located at on the ground floor of 79 Tithebarn Street, Liverpool, L2 2ER.

Click through for:

- Accessible Text for the exhibition.

- Timeline Credits for sources which aided the creation of this timeline.

- Extended Bibliography of more reading on the history of nursing studies in and around Liverpool.

Accessible Text

Liverpool Royal Infirmary – 25 March 1749

The Earl of Derby opened Liverpool’s first voluntary hospital, the Liverpool Infirmary, at Shaw’s Brow, now the site of St George’s Hall. This was the ninth voluntary hospital to be built in Britain. There were 30 beds and construction of the hospital was funded through subscriptions from the town’s doctors, ship owners, and merchants.

Florence Nightingale 1820-1910

Florence Nightingale was born on 12 May 1820. At age 16, inspired by her religion, Florence experienced a call to service to become a nurse, although her family would not permit it. Nursing was thought of as a lower-class occupation during this time, and unthinkable for someone of Florence’s status. In spite of this, in 1853 she became a Lady Superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in London. In 1854, she left this post to lead the first team of women nurses sent to care for soldiers in the Crimean War. Nightingale had a close connection with Liverpool, sending 12 qualified nurses and 18 probationers from the Nightingale Training School for Nurses to Liverpool in 1865. In 1874, she wrote to William Rathbone ‘at such a place as Liverpool the advantage is that there is an ‘espirit de corps’ or rather ‘de ville’…What fulcrum is there for any organisation to compare with your nursing organisation in Liverpool?’

A memorial was erected in Liverpool to Nightingale in 1913 as a celebration of her ‘great personality… her wonderful sympathy, her enthusiasms, which were always young, her simple and modest attributes, and her perfectly ordinary courtesy.’

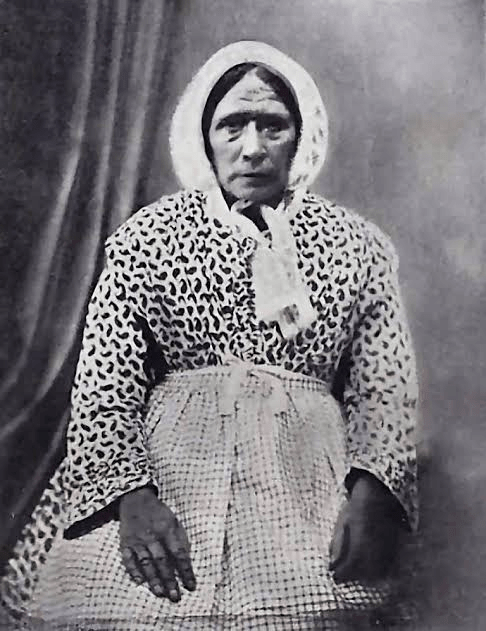

Kitty Wilkinson

In the 1830s-1850s, refugees and migrants from Ireland made up a large portion of Liverpool’s increasing population. Kitty Wilkinson, originally of Londonderry, was later known as the Saint of the Slums for her public health initiatives in the city. During the 1832 cholera epidemic, Wilkinson offered the use of her boiler, yard, and house to neighbours, to wash their clothes, and taught the use of chloride of lime in cleaning. She was convinced of the importance of cleanliness in combatting disease and was supported by the District Provident Society and William Rathbone, a wealthy Liverpool philanthropist.

Liverpool Northern Hospital – 10 March 1834

The early 19th century saw rapid expansion in the northern side of Liverpool, due to a growth in population and increased activity in the dock area. This created the need for a new Northern Hospital, which opened on 10 March 1834 at 1 Leeds Street. The hospital began with only 20 beds but by 1838 had grown to house 106 beds.

Medical Officer of Health Dr Duncan

Through the passing of an Act for the Improvement of the Sewerage and Drainage and provisions of further sanatory regulation in Liverpool, the Town Council created the first Medical Officer for Health post in the country. Dr William Henry Duncan, a doctor and former physician at the Liverpool Infirmary, was the first to hold the post. Dr Duncan was an early pioneer of public health reform and his work was inspired by his desire to prevent the physical, social, and cultural causes of disease.

Liverpool Women’s and Maternity Hospitals – November 1841

The Liverpool Maternity Hospital, first named the Lying-in Hospital and Dispensary for the Diseases of Women and Children, opened in 1841. The hospital was built on Horatio Street, Scotland Road, before transferring to Pembroke Place in 1845. New premises were soon required and a larger hospital was opened on Myrtle Street in July 1862.

Liverpool Southern Hospital – 17 January 1842

The Southern and Toxteth Hospital opened on Greenland Street with only 30 beds. Expansion was soon required and was funded largely through a concert given by Jenny Lind at the Royal Amphitheatre in January 1849.

Dickens’ Sarah Gamp

Caricatures like Charles Dickens’ Sarah ‘gin-guzzling’ Gamp represented the archetypal nineteenth-century nurse: with a nose that was ‘somewhat red and swollen’, and ‘a smell of spirits.’ This stereotype of nurses as untrained and uneducated was challenged by reformers like Elizabeth Fry and Florence Nightingale, who improved the nurses’ image by professionalising the workforce through training and education.

1850s-1860s

This period saw rapid population growth and extremes of poverty and wealth in Liverpool, due to the expansion of the city’s maritime trade and an influx of migrants. By 1860 the population had ballooned to almost 400,000 from just over 300,000 in 1851. This had a detrimental effect on the quality of healthcare available to the city’s inhabitants, and this was felt most by the poorest citizens who occupied slum dwellings.

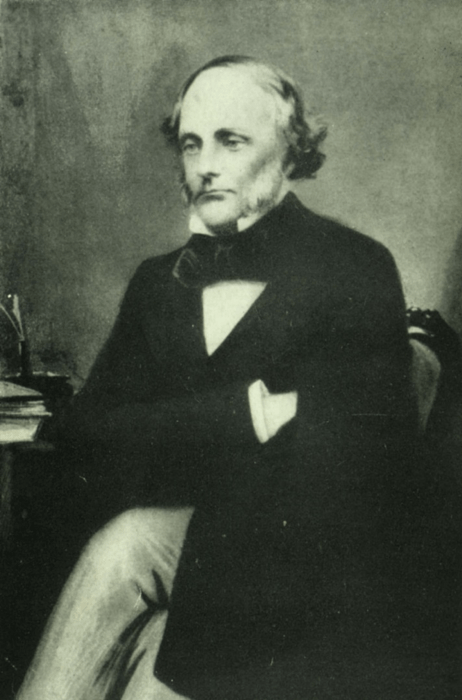

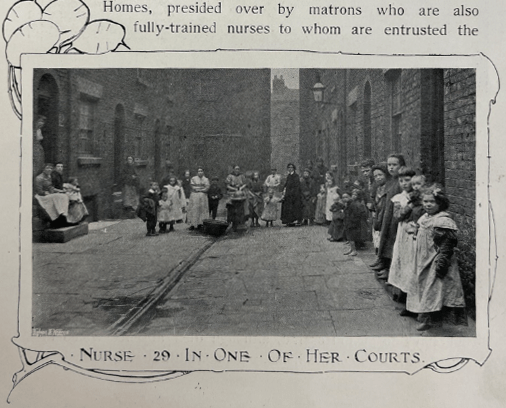

District Nursing

William Rathbone employed Mrs Mary Robinson to look after his dying wife in 1859. In his memoir, Rathbone wrote how ‘deeply grateful’ he felt ‘for the comfort which a good nurse had been to my wife’ and ‘what intense misery must be felt in the houses of the poor for the want of such care.’ Rathbone was a major supporter of a trained nursing service which could be deployed to tend the sick-poor in their homes. He subsequently created a system of home nursing in Liverpool and planned 18 districts where a ‘district nurse’ would be stationed.

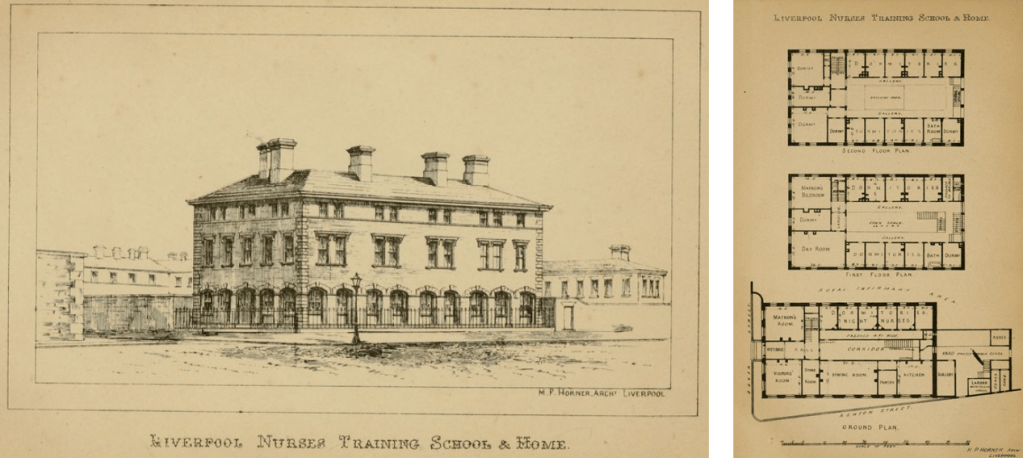

Founding of the Liverpool Training School and Home for Nurses

William Rathbone helped form the Liverpool Training School and Home for Nurses with Florence Nightingale in 1862. The School was attached to the Royal Liverpool Infirmary to provide thoroughly educated professional nurses to work in the infirmary, outside in the district, and for private families. Nightingale published her account of the Training School in 1865.

Agnes Jones

Agnes Jones answered Florence Nightingale’s advertisement for women of good character in The Times and was accepted as one of the first twelve probationers at the newly established Liverpool School of Nursing in 1862, the only Irish woman to start that year. Jones caught typhus during her nursing duties at the local workhouse and died in 1868. She is commemorated in the window on the staircase leading to the Lady Chapel in Liverpool Anglican Cathedral.

1867

The Stanley Hospital, first named Hospital for the Treatment of Diseases of the Chest and Diseases of Women & Children, was built on Stanley Road, Kirkdale in 1867. The construction was supported by voluntary contributions from the general public. The original hospital building was closed in 1873 and a new building was erected on the Stanley Road site in 1874.

21 May 1872

Although there were multiple attempts at renovation and expansion, the original premises of the Southern Hospital were insufficient. A new hospital was therefore opened on Caryl Street in 1872 as the Royal Southern Hospital.

10 August 1883

The Special Hospital for Women was opened on Shaw Street by the Countess of Sefton. In 1932 the new Women’s Hospital was opened on Catharine Street by the Duchess of York and merged the Shaw Street Women’s Hospital with the Samaritan Hospital for Women on Upper Parliament Street.

13 November 1889

The new Liverpool Royal Infirmary was opened. The hospital featured many state-of-the-art innovations, such as glazed brick interiors, patented fireproof floors, and steam heating throughout. Florence Nightingale advocated for high ceilings and stables for horse-drawn ambulances.

1898

Nurse training schools were established at the Northern (Leeds Street) and Royal Southern (Caryl Street) Hospitals.

Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine 1898

The Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, the first institution in the world dedicated to research and teaching in tropical medicine, was founded.

1902 Midwives Act

The 1902 Midwives Act created the Central Midwives Board, responsible for the registration, training, and regulation of midwives and their practice. This move was seen as a response to unfavourable caricatures of midwives, similar to that of Sarah Gamp, Charles Dickens’ caricature of a nineteenth-century nurse.

Early 20th Century: Health in Domestic Science

F L Calder College of Domestic Science (1875-1976) was one of LJMU’s founding colleges. The College worked with the St John’s Ambulance Association, where Fanny Louisa Calder was Secretary, to offer students training in Home Nursing and First Aid alongside Science & Health Education courses. Their approach reflected the gendered expectations on women to provide care at home and supported women’s contribution to the home front effort during the First and Second World Wars.

1914-1918 World War One

The war effort brought thousands of women to the wards of Britain’s hospitals, many through membership of the Voluntary Aid Detachment. The College of Nursing was also founded during WW1, which advocated for the nursing profession to be organised and regulated, although not necessarily through a professional register.

Pioneering Paramedicine in Liverpool

In 1883 the Northern Hospital in Leeds Street ran the first UK service using medically equipped horse-drawn ambulances. Credit for this is given to surgeon Reginald Harrison, inspired by a similar service in New York. In the first five months the ambulance dealt with 186 cases, but within a year over 1,000 calls had been attended. By 1890, horses and drivers were stationed at Central Fire Station, Hatton Garden, Northern, Southern and Royal Infirmary Hospitals, as well as throughout the wider Liverpool area. In 1916 horse-drawn ambulances were replaced by motor ambulances.

Professional Regulation: The General Nursing Council

After a long-fought campaign, a General Nursing Council was established, following the Nurses Registration Act 1919. The act sought to solve concerns about the lack of standardisation and regulation. It introduced a register, which only included nurses who had gained a certain level of relevant education and experience. The Act’s supporters believed the register would improve patient care by preventing nurses who were not adequately trained, or those who regularly violated standards of practice, from working in UK hospitals.

Unifying Liverpool’s Hospitals

In July 1937 the Liverpool United Hospitals Act received royal assent. This amalgamated the four Liverpool voluntary hospitals (the Royal Infirmary, David Lewis Northern, Royal Southern, and Stanley Hospitals) into a single body. In 1948, the governing body, The United Liverpool Hospitals, was established as a ‘teaching hospital’, administered by a Board of Governors appointed by the Ministry of Health.

1939-1945 World War Two

Liverpool was expected to be a primary target for aerial bombing, with the David Lewis Northern and Royal Southern Hospitals near the docks believed to be especially vulnerable. At the advent of war, there were nearly 50 hospitals across Merseyside, providing over 9,000 beds. These were split between the four teaching hospitals (Royal, Northern, Southern, and Stanley), and the larger municipal hospitals (Fazakerley, Walton, Mill Road, and Smithdown Road).

The Southern Hospital was evacuated to premises in the Fazakerley Hospital for Infectious Diseases in 1939 and did not return to Caryl Street until 1950. During the war the Caryl Street site was used by the Admiralty as a training school for merchant navy gunners and was named H.M.S. Wellesley. David Lewis Northern Hospital was relocated to St Katherine’s Teacher Training College in Childwall.

1948 The National Health Service

The National Health Service was introduced under the 1946 NHS Act. This established a health service to secure improvement in the physical and mental health of the people, and the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of illness, free at the point of care. Since its creation, the NHS has depended on the talents of a diverse and skilled workforce.

1948-1970s: Diversifying the Profession

Following the first migratory ship HMT Empire Windrush, which brought Caribbean men and women to the UK for work on 22 June 1948, and the joining of Male nurses to the GNR in 1949, Liverpool experienced a noticeable diversification of its student nursing population. Migrants from the Commonwealth of all genders soon filled the student registers of Merseyside.

1970: Liverpool Polytechnic is Established

Plans for a polytechnic began in the late 1960s, before being established on 1 April 1970. The Liverpool Polytechnic offered a vocational approach to higher education, concentrating first on science and technology. Over time, the composition and identity of the Polytechnic grew and developed.

1970s: Residential Training for Students

Students at District Nursing Training Schools, such as St Helens and Whiston School of Nursing, often lived on site in residential homes for student nurses.

1978-1979

In 1978, after decades of proposals, The Royal Liverpool Hospital opened to replace the Liverpool Royal Infirmary, David Lewis Northern, and Royal Southern Hospitals. A single Liverpool District Area Health Authority was formed, and the Liverpool School of Nursing replaced the District Schools of Nursing in 1979. That year, the United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery & Health Visiting also formed to bring the three together under the same higher education training model.

Professional Regulation: The UKCC and Project 2000

The General Nursing Council was replaced by the United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (UKCC) in 1983, and in 1986, Project 2000 launched. Student nurses were now no longer counted as staff required for safe and effective care on hospital wards. Project 2000 replaced the old apprenticeship State Registration training and created the new Registered General Nurse. In April 2002 the UKCC was replaced by the Nursing & Midwifery Council.

1991

The College of Nursing and Midwifery joins the Liverpool Polytechnic.

1992 Onwards: Liverpool John Moores University

The Further and Higher Education Act of 1992 transformed Liverpool Polytechnic into Liverpool John Moores University, one of the first to receive a royal charter on 1 September 1992. The Liverpool School of Nursing and Midwifery transferred authority over the nurse training schools formerly based at Broadgreen General Hospital, Royal Liverpool Hospital, Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, and Liverpool Maternity Hospital to LJMU. The Department of Nursing also combined with Central Mersey College of Health Care Studies, bringing together Whiston Hospital, St Helens Hospital, Warrington General, Winwick and Rainhill Hospitals’ nursing and midwifery training schools.

Advanced Practice

LJMU is as a major provider of midwifery, adult, child, and mental health nurse education, with over 900 pre-registration nursing students undertaking professional programmes at any one time.

September 2007

LJMU ran its first degree programme in Paramedicine. LJMU retains close links with the North West Ambulance Service, local acute hospital trusts, and primary care trusts to develop programmes for paramedics and ambulance staff which reflect the increasing emphasis on pre-hospital care.

LJMU’s Health Village

LJMU has invested £1.6million to develop its current Health Village on campus. The Health Village consists of clinical practice suites and enables students to treat virtual patients in a range of simulations from home environments, roadside accidents, ambulances, A&E, and rehabilitation back into the community.

COVID-19 Pandemic

Health professionals and trainees were committed to making a difference during the COVID-19 Pandemic, focusing on LJMU’s core values of community and togetherness. During the pandemic, Nursing and Allied Health students helped on the front line in hospitals and health centres throughout the country. LJMU donated large supplies of personal protective equipment including medical gloves, aprons, hand sanitisers, examination gowns and more to hospitals within the region.

The reaction by staff and students to the Covid-19 Pandemic across the University, but especially within the Faculty of Health, exemplifies the long-standing and pioneering nature towards healthcare at LJMU throughout the 19th, 20th, and 21st Centuries. The events of the last 200 years have led us to where we are today.

Timeline Credits

We thank all of the following people for their hard work and contributions which made this display possible.

LJMU’s School of Nursing and Allied Health: Julie-Ann Hayes; James Owens; Ian Pierce-Hayes; and Lorraine Shaw.

LJMU Special Collections & Archives: Christopher Olive; Emily Parsons; and Susannah Waters.

Graphic Design from Apogee Corp by Kevin Carroll and Nuno Vale.

Images were reproduced from the following places (with permissions or licenses where applicable): LJMU Corporate Communications; LJMU Special Collections & Archives; William Rathbone’s Memoir of Kitty Wilkinson (1927); Wellcome Trust; The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910); and The National Archives.

Sources which aided the production of this timeline include: LJMU Special Collections & Archives; Wellcome Trust; The National Archives; Nursing Times; The Victorian Web; The Medical Memories Roadshow; and Liverpool Central Record Office.

Extended Bibliography

Abel-Smith, B, 1960. History of the Nursing Profession (London: Heinemann Educational Publishers).

Baly, M, 1986. Florence Nightingale and the Nursing Legacy (London: Croom Helm).

Belchem, J. (ed.), 2006. Liverpool 800: Culture, Character & History (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press).

Bickerton, T. H., 1936. A Medical History of Liverpool from the Earliest Days to the Year 1920 (London: John Murray).

Borsay, A., and Hunter, B., 2012. Nursing and Midwifery in Britain since 1700 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillian).

Brewer, C., 1980. A Brief History of the Liverpool Royal Infirmary 1887-1978 (Liverpool: Liverpool Health Authority).

Hardy, G., 1981. William Rathbone and the Early History of District Nursing: A Welfare Service 1859-1908 (Ormskirk: GW&A Hesketh).

Hawkins, S., 2010. ‘From Maid to Matron: Nursing, as a route to Social Advancement in Nineteenth Century England,’ in Women’s History Review, Vol.19 No.1, pp.125-143.

Martindale, J. H., 2020. ‘The United Liverpool Hospitals,’ The Medical Memories Roadshow. [accessed 2023]. Available via: https://medicalmemories.wixsite.com/medicalmemories/the-united-liverpool-hospitals

Meglaughlin, J., 1990. British Nursing Badges Volume 1: An Illustrated Handbook (Vade-Mecum Press). Jennifer Meglaughlin’s unpublished notes are housed at the Royal College of Nursing Archive.

Nightingale, F., 1865. Organization of nursing: an account of the Liverpool Nurses’ Training School, its foundation, progress, and operation in hospital, district, and private nursing (Liverpool: A. Holden). A digital PDF copy is available from the Wellcome Trust via: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/tygfd4zf

Parkes, M. and Sheard, S., 2012. Nursing in Liverpool Since 1862 (Lancaster: Scotforth Books). This is available via the LJMU Special Collections Library.

Parkes, M., and Sheard, S., 2012. Nursing in Liverpool Since 1862 (Lancaster: Scotforth Books).

Rathbone, W., 1865. Organisation of District Nursing in Liverpool (Liverpool: A Holden).

Schools of Nursing, n.d. ‘Liverpool Region Schools Timeline,’ [accessed 2023]. Available via: https://www.schoolsofnursing.co.uk/LiverpoolR74.htm

Shepard, J., 2019. ‘Past, present and future: The importance of nurse registration,’ Nursing Times. [accessed 2023] Available via: https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/centenary-of-the-register/past-present-and-future-the-importance-of-nurse-registration-08-10-2019/

Stocks, M., 1960. A Hundred Years of District Nursing (London: George Alwin & Unwin).

Webster, R., and Wilkie, S., 2017. The Making of a Modern University: Liverpool John Moores University (London: Third Millenium Publishing), pp.68-75.