After nearly 50 years, there is now a plaque in the Everyman to mark the contribution of Alan Dossor to the theatre. It is a small plaque, and it is hidden away on the very far side of the bar. You have to be lucky to find it. Or you have to know where it is – and now you do (have a look for it next time you are in the theatre). The quotation on the plaque, chosen by his daughter Lucy, reads “Theatre won’t change the world, but the people watching it just might.” It is a quotation from an interview Alan gave about one of his plays and it is a quotation that sums up the spirit of what he was trying to do in his five years at the Everyman.

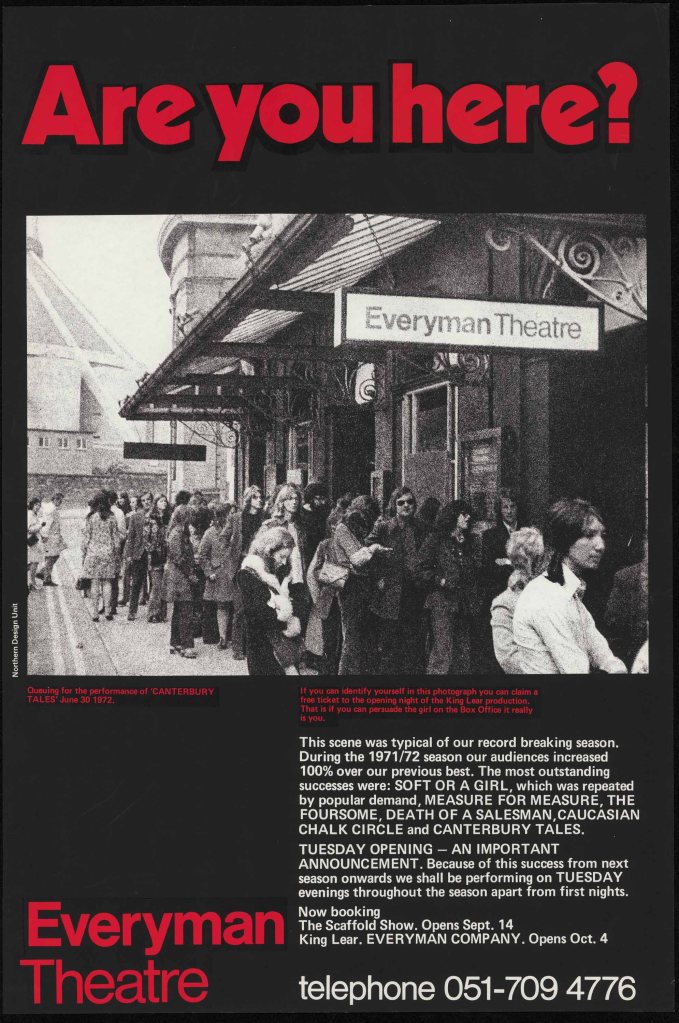

Alan Dossor arrived in Liverpool to take over the Everyman in 1970 at the age of 28. He inherited a theatre in a city that was retreating from its post-war golden age. The Beatles had long gone, and the global recession was starting to bite. The docks and manufacturing industry were in decline. Between 1966 and 1977, 350 factories in the city closed or moved elsewhere with the loss of 40,000 jobs. It was not an auspicious time to be taking over a scruffy building at the top of the hill on the way out of town, a theatre which was seen as being more connected to the University than the city and a theatre which was £5000 in debt and struggling with tiny audiences. Yet in his five years at the theatre, Dossor turned its fortunes around and his time at the Everyman has become known as a ‘golden era.’ His penultimate production in 1975, Willy Russell’s Breezeblock Park, not only had to extend its run but played throughout to 86% capacity.

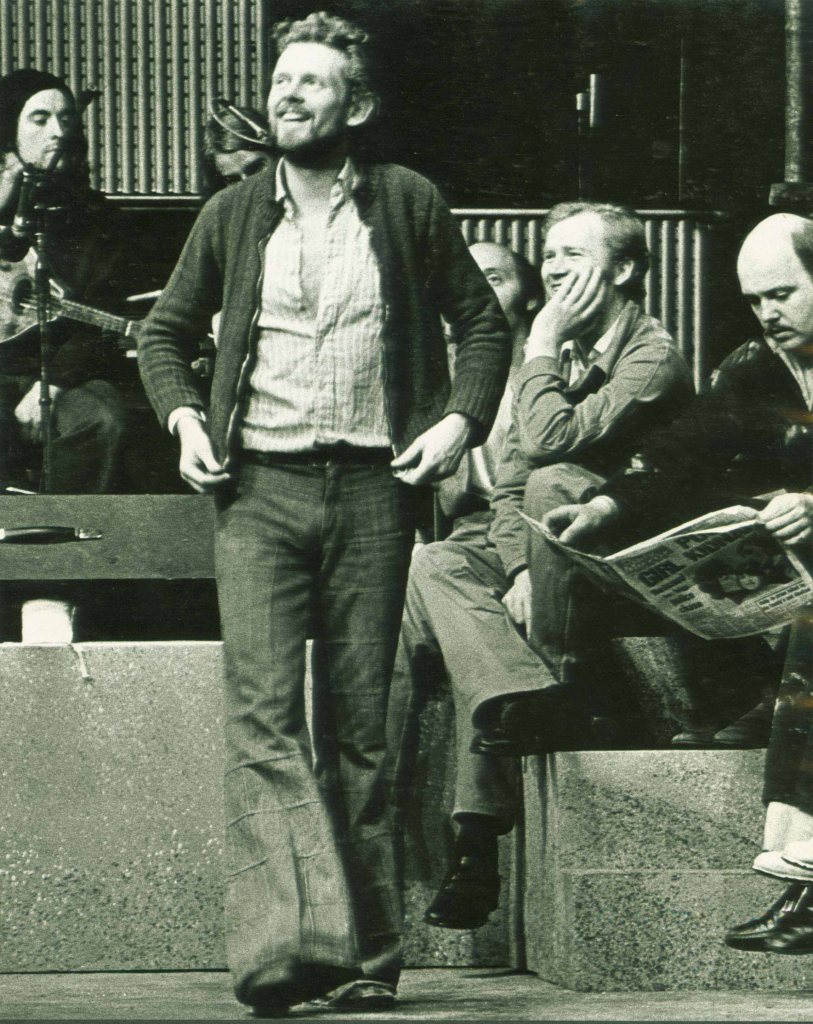

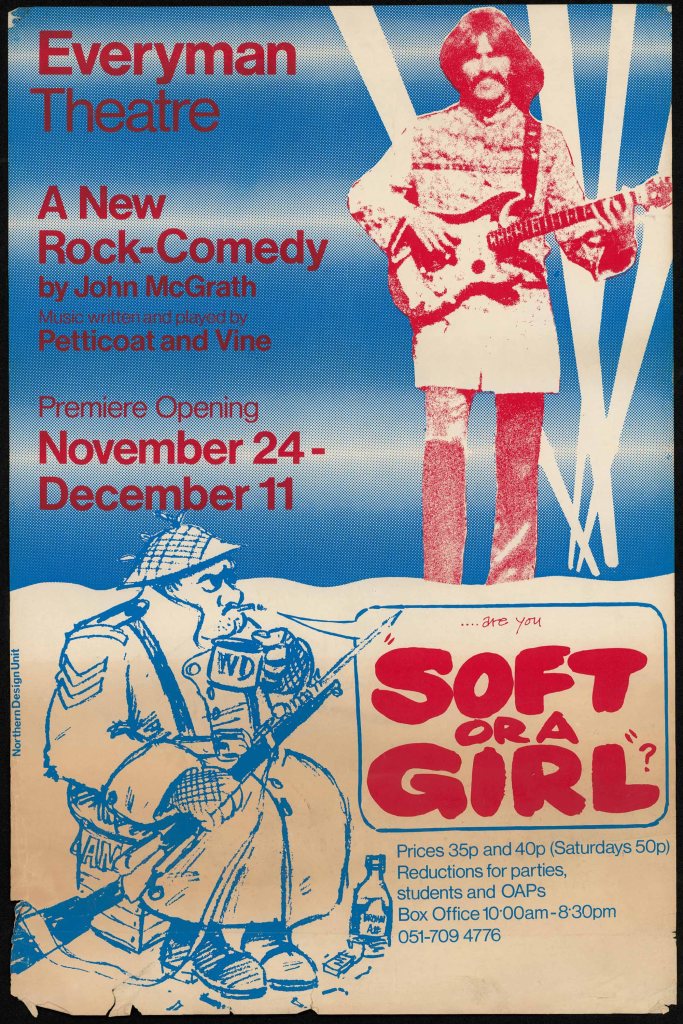

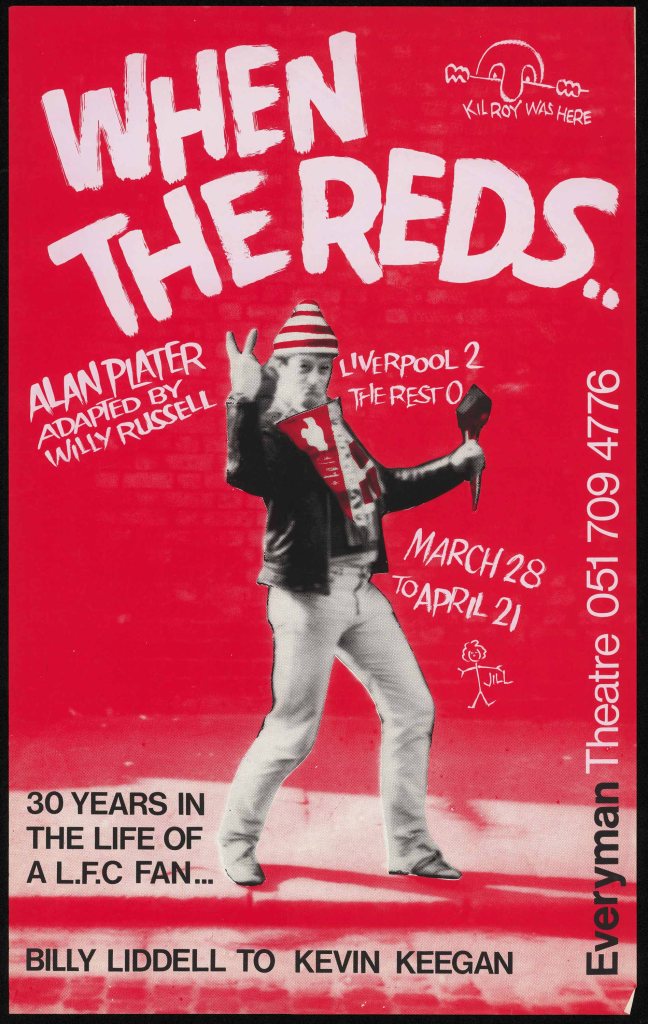

Dossor’s contribution to the theatre has been characterised in a number of ways. It is associated with the development of an Everyman house style, a style reliant on comedy, music, irreverence and, above all else, localism (we’ll come back to this!). It was a style that was informal, adventurous and popular. He is most often seen as having had a special talent for spotting talent and the list of actors he pulled into the company now reads like a rollcall of theatrical greats – Antony Sher, Jonathan Pryce, Julie Walters, Pete Postlethwaite, Bernard Hill, Matthew Kelly, Alison Steadman. He also assembled a pool of local writers. Birkenhead born John McGrath, who went on to run 7:84 theatre company, started writing for theatre at the Everyman. Unruly Elements (1971) was a series of five short plays linked together by a common theme – people faced with change. Soft or a Girl (1971) was Dossor’s first big ‘hit’ producing queues round the block and a swift return run. McGrath claimed the play played to 109% capacity and could have run for another 3 weeks. Willy Russell too started his professional career with Alan Dossor. He re-wrote Alan Plater’s football play When the Reds (1973), moving it from Hull to tell the story of Liverpool FC’s rise through 20 unbeaten weeks in 1949 to the 1964 FA cup win at Wembley. It was, ironically in a city so fond of its football, the first time a play about Liverpool FC had been staged. But it was his version of the Beatles story, John, Paul, George, Ringo and Bert (1974) that provided the theatre with their first West End transfer. Other writers joined the theatre including Adrian Henri, Brian Patten and Chris Bond, later to become the theatre’s artistic director.

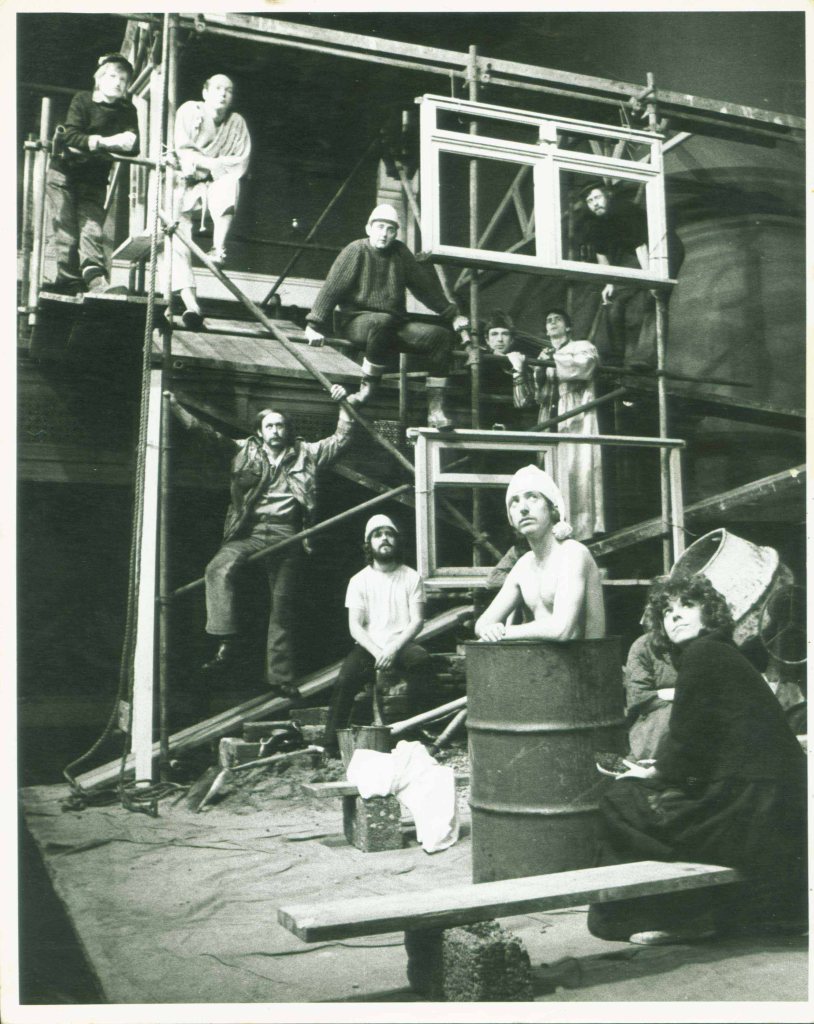

While new writing was key, Dossor also enjoyed re-inventing the classics making them seem as though they had been written specifically for the people of Liverpool. John McGrath was drafted in to re-write Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle (1972) turning it into a play which had a distinctly Liverpool and 1970s feel. Set on a building site, the play opens not with an argument about land, but with an accident on the site. A piece of scaffolding collapses and a building worker is taken to hospital badly injured. His fellow-workers down tools and stage a sit-in during which they are entertained by a troupe of not quite prepared actors who have turned up to see if they can come back and perform a play in three weeks’ time. It concluded that the building should go to the builders.

And those who will live in it: That

it shall be built for living in, not dying on

for people – not for profit.

Dossor’s Richard III (1973) was set in a lion’s cage; the characters were deemed to be so appalling that they had to be locked in a cage and allowed to tear each other apart. The play became a series of vicious executions with someone occasionally coming out and putting sawdust down saying, in Shakespearean language, that ‘things will only get worse, before they’ll get better’. The poster for the play showed a kneeling man having his feet hacked off, leading to one Wirral councillor raising objections, demanding that the theatre’s grant should be cut and declaring that posters like this must be contributing to the increase in juvenile delinquency. The Canterbury Tales had several outings. In the last it was renamed The Cantril Tales (1974) and set in the worst pub on Cantril Farm, a new overspill estate, where the arrival of Chaucer in a time machine was as welcome as a soggy crisp. Here stories were re-written by Dossor’s stable of writers including Willy Russell, Adrian Mitchell, Bill Morrison and George Costigan.

What unites all of the work and all of these narratives about Dossor’s work is its connection to the city and very often its ability to raise immediate concerns facing people in Liverpool. Dossor said he could never imagine doing a play without trying to connect with life outside. One of his key objectives when he took on the job was to try and establish a kind of dialogue with the city so that the Everyman really felt part of Liverpool. The Braddocks’ Time (1970), his second play was a musical documentary about the local MP Bessie Braddock, the Amazon of St Anne’s. Not so much a play, this was more of a contest; a fifteen-round boxing match which rendered all political activity in terms of violent contest in the ring paying tribute not just to Bessie Braddock’s battling spirit but also to the fact that she was honorary president of the Professional Boxers’ Association. With a company of twelve playing forty characters, it was played in a broad cartoon style, complete with red-nosed Tories. Over the next 5 years many plays about the city followed culminating in Dossor’s last production for the Everyman, Under New Management (1975). Chris Bond, as the writer, along with actors, interviewed workers at the Fisher Bendix plant in Kirkby which was under threat of closure following a series of takeovers and bad management. As Stephen Dixon noted in The Guardian it would ‘be hard to write an overtly serious play about what happened at the Fisher-Bendix factory, a place where at one point eight stainless steel sinks were produced at a cost of £25,000 each due to appalling inefficiency and squandering on the part of the management.’ (6th June 1975). The company had already been to the factory in 1972 when they performed extracts from Soft or a Girl for the workers during their occupation. Now, they brought the workers and their story onto the theatre’s stage complete with a Bendix tumble dryer and an extended sketch, The Ivor Made a Million Show, which comically explained how Ivor Gershfield had managed to make so much money from taking over the company whilst at the same time stripping it of all its assets.

Connections to the city weren’t always about people coming into the Everyman to see a play about Liverpool. They were also about the theatre going out into the city. Newly arrived actors were routinely taken to visit factories and into different communities to get to know the people. Long before ‘community theatre’ was seen as a key part of a theatre’s brief, Dossor set up Vanload writing in ‘The Everyman Theatre: A Case for Expansion’ that:

It is necessary if we are to fulfil our role, for actors and directors to come in direct contact with the people of the community. The Everyman cannot properly progress until we have a situation where we can replenish our ideas and aims by meeting the people whom we have now successfully brought in to see the plays. (EVT/A/R/000003)

EVT/P/000357 Everyman Theatre Archive, LJMU

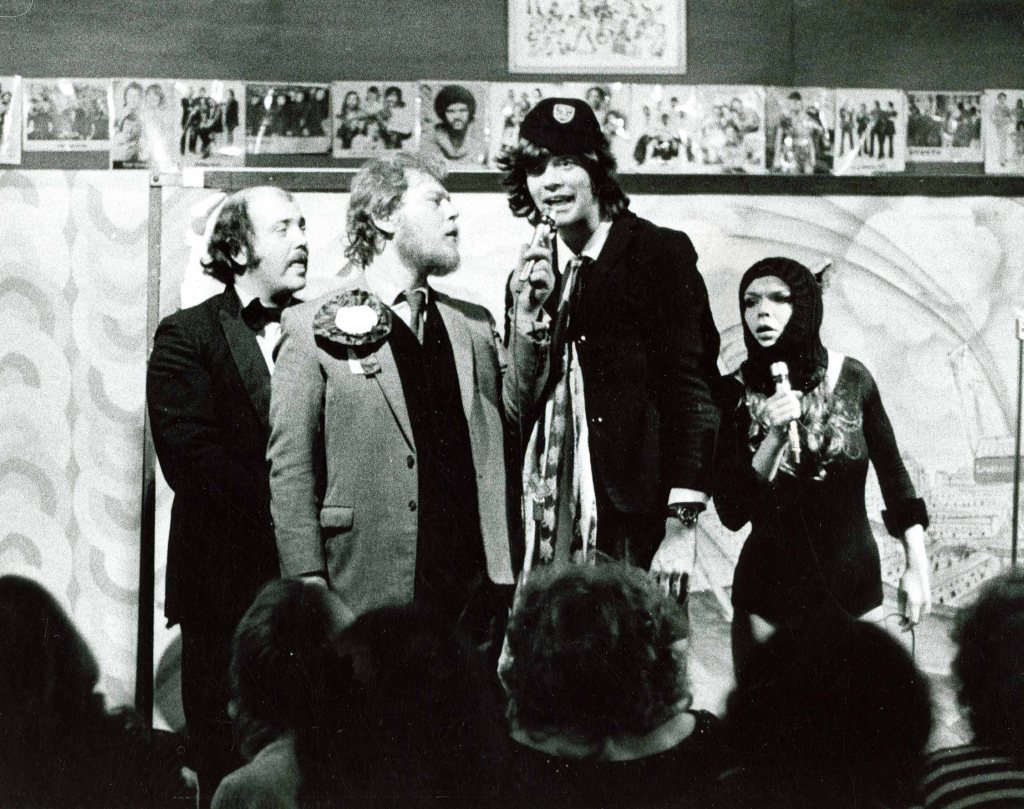

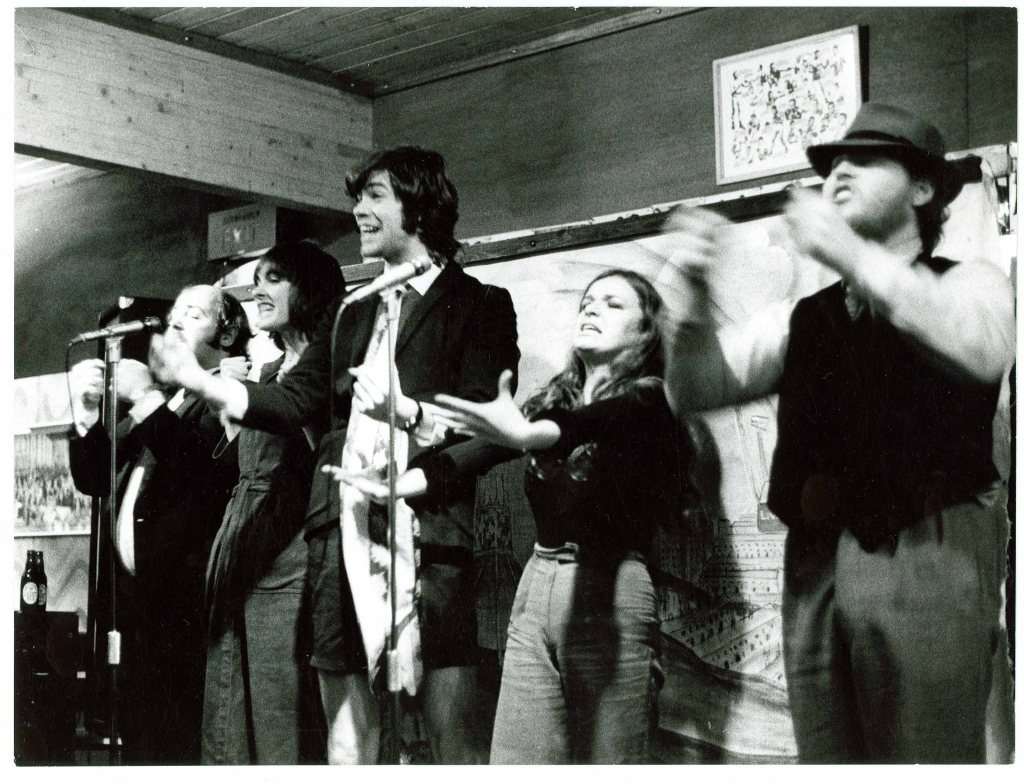

Vanload was made up of members from the company who alongside performing in the theatre also went on the road to pubs, clubs, schools and community centres. It allowed them, as Dossor says to ‘replenish their ideas’. It also allowed parts of the city without theatre to see performances. The plays written by the company for Vanload might also raise some eyebrows but as much as the plays on the main stage, these too reflected Dossor’s hope that the people watching might be the ones to change the world – even if they were often very young. Their first venture, The Battle of Lumbertubs Lane was for junior schools touring to schools in Croxteth, Kirkby, Toxteth and Wigan, telling a story (with pupil participation) about tenants taking on unscrupulous landlords. The Slick by Chris Bond and the company was a documentary about the Shell oil company’s plans to build a huge oil installation off the coast of Anglesey. And The Gravy Garden told the story of a fat man called Glut who eats too much but never feeds his servants.

EVT/P/000357 Everyman Theatre Archive, LJMU

Why is all this important? While Alan Dosser’s time at the theatre is often seen as a golden age, his legacy isn’t well-known. He might be fine with that. As his daughter Lucy has said of her father, ‘he would have said, tear it up, it’s bullshit, it’s the past, move on, do now. This is why the sign is hidden. He disrespected idolatry, celebrity, reverence.’ Yet, his five years at the theatre has much we can learn from. He turned the theatre from one that was struggling to one to one where, as Julie Walters remembers, people came in their droves. On the last night of Under New Management, one of the audience members remembers the evening ending with people staying and singing songs with the band: ‘We became the theatre, ordinary people. The Everyman was brilliant at that.’

Now, we are at a time when many theatres are struggling to find their place as they juggle with declining funding and post-covid recovery and audiences struggling to find money for tickets. The city, of course, is in a different place to where it found itself in the 1970s but this is a story which seems worth revisiting now. And the archive might hold some clues to the way forward.

Dr Ros Merkin, Head of Drama, LJMU & author of “Liverpool’s Third Cathedral: the Liverpool Everyman Theatre in the Words of Those Who Were, and Are, There” (2004)